At 5am, our alarms went off, and we got out of bed as quietly as we could, even though we could hear noise out in the hall. Members of the tour group were already up and getting dressed, with people shuttling to and from the bathroom (located outside). Greta came downstairs to the kitchen and turned on the stove.

“They turned the gas on,” she said. A sign that they supported our early move? Maybe. Either way, Mel and I were speedily packed and on the way out with nothing but a Clif bar to start the day. (We even forewent coffee. That’s how eager we were to not get caught in the storm.)

Amazingly, our boots were dry. A night on the radiator did them well, and I slipped the soles back into them and when I put my feet in, they were warm! Today, we donned our rain pants immediately, covered up our backpacks with the rain covers, and put on our rain coats. Outside, the world was covered in a cloak of mist. The rain was there, but it was more of a persistent mist-drizzle than the assault we’d faced the day before. At first, I was a little nervous heading out on our own, with nothing but a sign pointing us on our way.

The trail is well-marked with wooden posts, the tops painted in a different color (the first day it was red and yellow, but it eventually changed to red, and then to blue). We could only see the nearest pole through the curtain of fog, but we pushed on anyway.

The Dutch men were also up and behind us a short way, so we felt bolstered by the fact that we were not alone. Every so often, we’d stop at the top of a snow ridge and scan the fog for a post.

“There’s one,” Mel would say, pointing at a fallen pole. “It just fell down.”

We took the snowfields carefully today, looking to see where the snow looked more packed than thin. I learned from my book that just because there are boot prints across the snow, it doesn’t mean it’s safe to walk there. It might have been sturdy when the prints were made, but might be decaying now.

The rain stopped, but the wind persisted. There were several occasions where we’d be ascending a hill on a slice of path that hugged the edge and dropped off down below, a knife’s edge ridge, and suddenly a gust of wind would barrel down on us. We’d plant our hiking poles into the path and squat down to avoid falling over.

Wind, you might be thinking, that can’t be so bad.

A little note on Icelandic wind: when you rent a car here, you are warned to open the doors slowly, because the wind has been known to rip doors off their hinges. Years ago, when I stayed at a farmhouse, the owners told me how their SUV, parking brake on, had been pushed down the driveway by a fierce wind storm. And of course, there was the December a few years back when Allison, Kacey, and I had wheeled our suitcases from the airport to the rental car and the wind had literally lifted my suitcase into the air.

In short: a puny human on a mountain ridge is a dandelion puff to Icelandic wind.

At least it wasn’t raining.

We slogged onward, my boots sinking into rhyolite mud that looked like cake batter. At least the mud was cool – the rhyolite in the dirt meant the mud was teal, blue, and pink. It was like stepping in confetti cake batter.

All morning, we traded places with the Dutch men, overtaking them, then falling behind them. They’d come down behind us and we’d point out where to cross a snow field, or they’d move ahead of us and show us where the path led.

The rain pants were a game changer. No amount of wind or water could penetrate my warm, dry legs now. The wind pants kept me shielded. I’d also put on my underarmor, so my whole body was warm.

It was a strenuous climb to get up the hill, and we were both aware that we were working against the clock to get to the next hut at Álftavatn, a beautiful lake whose name translates to “Swan Lake”.

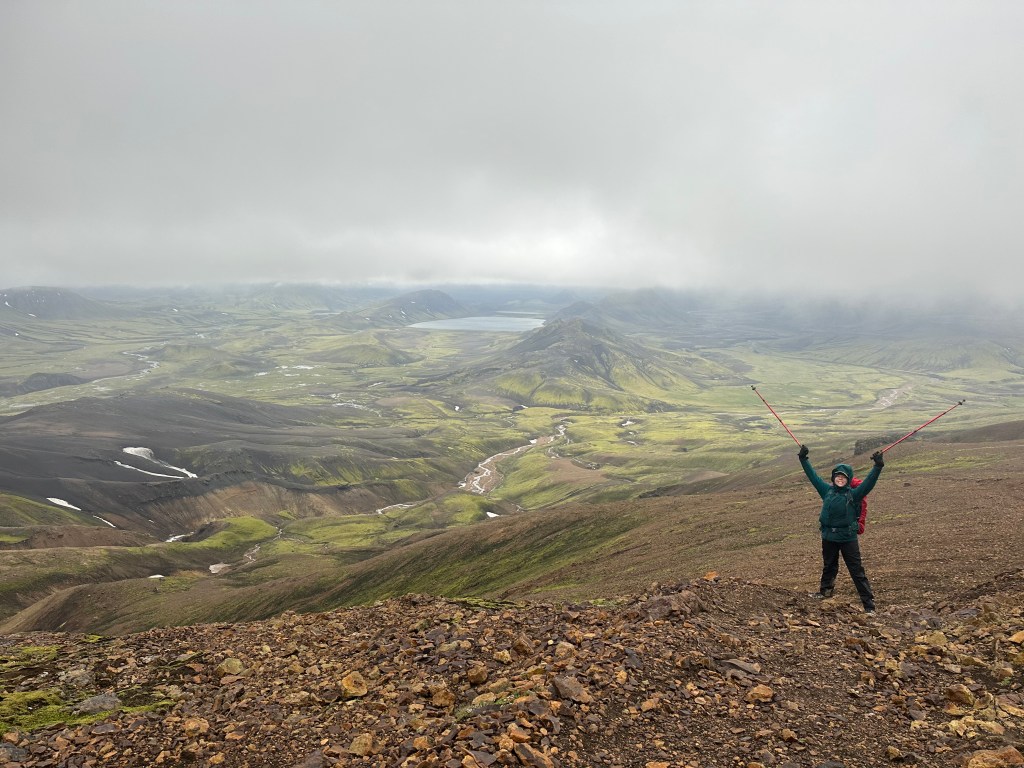

As we sweatily crested another hill, we both looked up and gasped. It was as if we’d beheld God: way down below, like a lost kingdom, was the verdant valley where our huts were visible beside a rectangular stamp of blue lake. And down in the valley, the green hills and fields and the burbling rivers were dappled in sunlight. SUN!

There was shrieking, exclamations of joy, photographs, and an abrupt change in tone. From the windy, foggy, rugged ridges and snow fields, we were suddenly viewing emerald and sun and hope. Our moods went from “must-persevere” to “ohmigod get me down into the valley!”

My book had promised that as we descended, the temperature would get warmer and the wind gentler, and both were true. The descent was steep in parts, but gorgeous. The path was rocky and wound its way through green moss, grass, and bright flowers like lupine and sea campion.

We were practically skipping down the mountain into the valley.

And then we came to our first river crossing of the trip. We’d been told that this crossing had “string”, something to hold onto. When we reached the crossing, the Dutch men had just completed it and seemed in good spirits. The breaking clouds above and the promise of our hut just over the next hill put us in good spirits, too, so we found a rock and got ready.

We rolled our pants up above our knees, removed our hiking boots and socks, and pulled out our water shoes. Mel had an awesome, closed-toe pair of Keens, and I had my open-toe but secure Tevas. The author of the book – Brian, and so I will call him that from now on – had emphasized the importance of good footwear when crossing rivers. He mentioned lost and broken toenails as a good reason to invest in sandals and never, he asserted, cross barefoot.

We tied our hiking boots to the clips on the side of our backpacks and waded in. The water was predictably very cold, but our moods were up; we whooped at the cold and laughed and easily crossed to the other side, where we sat on a rock and changed shoes.

As we did this, three hikers came down from the other side to cross back to where we’d come from. One of them changed quickly into her river shoes, then looked at the water and sighed.

“You can do it!” we encouraged her.

“Oh, I know,” she replied. “It’s just that I’ve already done this three times and I don’t want to do it again. And one river back there, just beyond the hut, is up to here.”

She pointed to her waist. This was frightening.

“Is there a string?” I asked. She shook her head.

“Just take small steps and use your poles,” she told us.

We laced up our hiking boots and headed on, emerging just on a hill overlooking the huts at Álftavatn. We checked in at the warden’s hut at 10:30am. Check-in is normally at noon, but the warden was probably there for check-out, which is until 10:00am. Excited to have beaten the weather – and remained dry! – Mel and I ordered a beer, a Pepsi, and a Snickers bar to celebrate.

“Your room is upstairs,” the warden told us. “Room 6.”

We headed into the hut, placed our boots by a furnace, removed the soles, and headed upstairs to our room.

Unlike the night before, this room was basically one long aisle of floor with beds on either side, all lined up. Mel and I chose a bed with two mattresses on it, closest to the door. There was a small gap between our bed and then one long row of wood where all other mattresses were placed side by side. Our Dutch friends had already secured their beds. It was nice to see them, but we realized we’d be sharing with a tour group and we missed our pals from the night before.

Immediately as we sat on our beds, the rain began.

Between 10:30 and 12, all of the other groups arrived. The last group to arrive, Greta’s group, had come up over the ridge as the storm began, and missed the green panorama that had given Mel and I so much hope. We felt for them.

Not enthusiastic about hanging out in our dorm room, Mel and I took a bag of beef jerky downstairs to the common kitchen area, as well as two bags of porridge, and had lunch. We passed around the beef jerky and chatted as our new friends arrived.

Unlike our last hut, this one offered showers; for free, you could stand beneath ice cold water for as long as you wanted. For 500 IKR, you could have five minutes of hot water.

When I am camping, I can go without a shower for the entire trip. I don’t mind getting in touch with my dirtbag self. Mel, on the other hand, insisted on showers. For her, she emerged a new person.

Something about the way she described this, or maybe my concern that I smelled and Mel was too polite to tell me, pushed me to get a shower, too.

We grabbed our things and ran into the showers, only to find that we’d needed to buy the voucher from the warden. I told Mel to wait in the shower, and I’d go grab the vouchers. I sprinted back to the hut, where Greta’s group was arriving and passing the luggage from the van into the hut. I weaved between them, apologizing, explaining my situation with the shower.

I finally got my debit card, ran to the warden’s hut, and saw a sign on the door: wardens were out to lunch.

Eventually, we got our hot showers, but it was pouring rain, so the cleanliness was short-lived as we sprinted back across the boards into the hut.

We sat around the table with the Australian family and a solo traveler, Holly. Holly had set off like us, with a friend she’d met at a hostel. But they hadn’t booked huts, so her friend was forced to tent camp the night before when they drew straws to see who would take the last bed in our hut and Holly won. The friend turned back, but Holly decided to push on by herself, hoping for the best.

The game we played was called Presidents and Assholes, or something, but everyone who had played before had a different idea of how to play, and the rest of us sat looking on in confusion for a good twenty minutes before we started the game.

The weather for the next day was looking less stormy, but there were river crossings to be done, and conflicting information about what these looked like.

On the sign at the warden’s hut, which had a hand-drawn map, there were two river crossings, and both were knee-deep or ankle-deep. But a French family who arrived quite late and drenched and were unpacking in our shared room told us that they’d crossed three rivers that day.

Then there was the woman who had told Mel and I about the waist-high river. Unsure of what to expect, I let it go. There wasn’t any new information I’d find between now and then.

It was a long afternoon, having arrived so early, and it took a while to get tired. I had just nodded off to sleep when I was startled awake by a snoring so deep, textured, and concerning that I could not fall asleep again.

This man inhaled like a motorcycle revving, and then exhaled as if he were a hungry ogre about to climb down a beanstalk to eat a small human.

On his exhale, as if on cue, another snorer struck up an inhale, and soon it was a cacophony of snoring, choking, and various other grotesque mouth and throat sounds. It was like sleeping in a garage full of F1 cars running their engines, and some were clogged with oil or broken.

To make matters worse, the group had decided that it would be best to close the one window in the room and the one door, so we were all sealed into an airtight box where our germy, disgusting breath could mingle as one hot, moist entity that we could happily inhale all night long.

I had to escape, so I left the room with the door open and ran out in the pouring rain to the bathroom just to gasp some clean, cool air. It was past 10pm, but the sky was still light. (The sun doesn’t really set up here in the summer.)

When I came back, someone had closed the door. Someone was desperate to breathe in the exhalations of two dozen strangers. Luckily, Mel woke up around then and opened the door again.

According to her, it was a battle through the night. Someone would leave and close the door, and Mel would open it again.

“In the middle of the night, a man sat up and said, ‘Just for the record, that isn’t me,’” she told me.

While Mel slept, I heard an old woman stirring a few beds over. She suddenly sat upright and said, “Oh, Leonard! I just don’t know.”

Then she flopped down again, tossed and turned in the sleeping bag, and muttered a few other troubling sounds before dozing off again. When I awoke the next morning at 6, I immediately brought my bag downstairs to pack. Nothing gets you moving in the morning quite like a room full of hot strangers pressed against one another, snoring so loud that the high-pitched, whistling wind outside has met its match.

Categories: Iceland